|

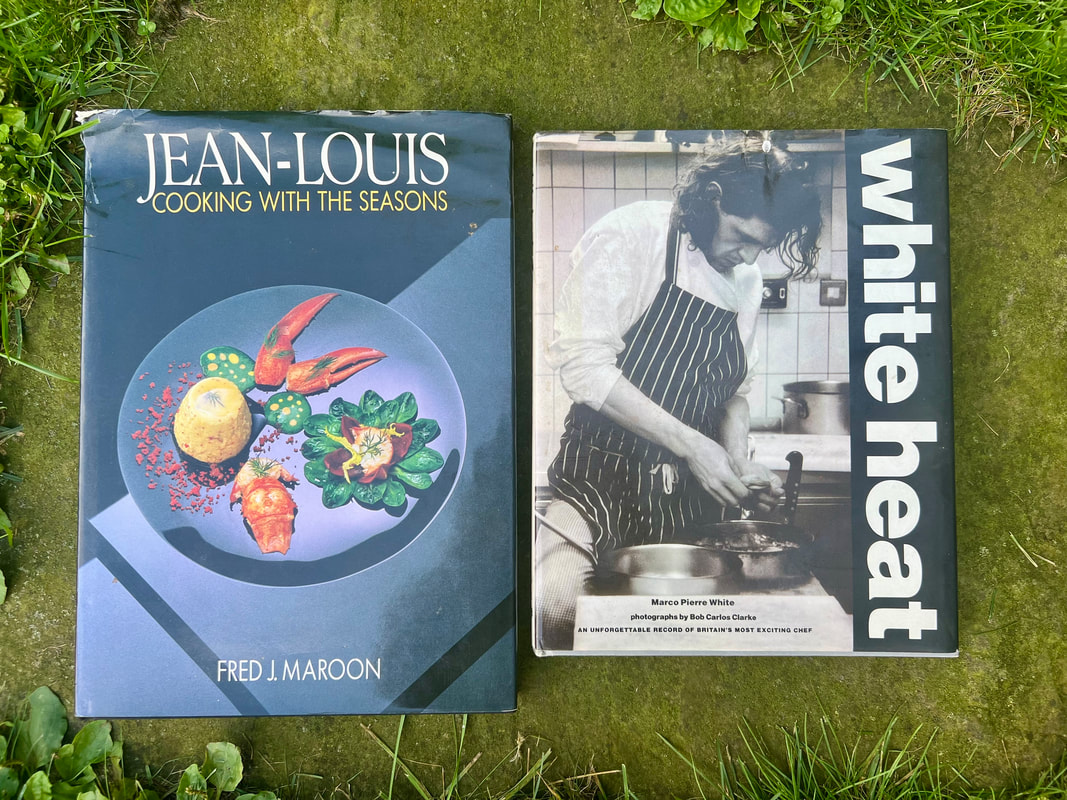

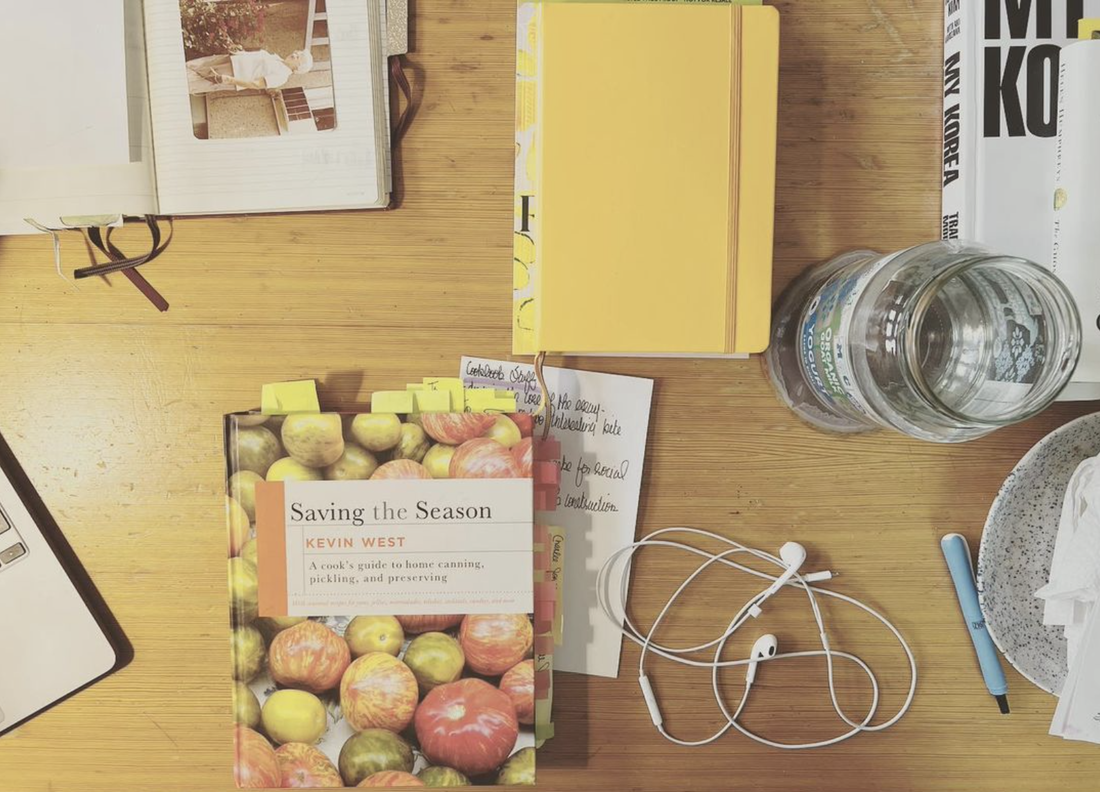

These are threads I'm pulling on. Reading one thing and linking it to another. Trailing the scent of connection in the quiet. Thank you to Claire Dederer for writing this brilliant book with forthrightness. It should be on the New York Times Bestsellers list. The bold quotes are from Chapter Five, The Genius. *** Both cookbooks are first editions. I was hungry when I bought them. Insatiable is closer to it. I wanted it all. Twenty-seven years old and working garde manger and pastry at Le Bistingo on Queen St. W. when it was top spot in Toronto. Shucking Fine de Claire oysters flown in from Brittany and whipping Calvados sabayon to renaissance clouds. I was months away from going to the Stratford Chefs School. *** "And yet—isn't the genius the person who changes everything about his or her field? Thomas Kuhn called this a paradigm shift, before the word "paradigm" got taken over by corporate dipshits and lazy undergrads." They were wild, obsessed, sexual men. Look at the photo of Marco, the oil stain on the knee of his houndstooth chef pants. The jacket looks like he never leaves the kitchen. I imagine the thick cotton slightly damp and smelling musky. In the afterglow of dinner, a trail of women in stilettos and petit four dresses wander through his kitchen. Who will ever forget Jean-Louis Palladin's "get-me-the-Vitamix" moment? Palladin's book is tall and lanky, like the man and his blender. It needs a big coffee table. The cookbooks cum art books were released within a year of each other. When I look at the food, Harvey's is still everything I want in a restaurant. If you have White Heat, go get it and turn to page 73. That dish is pure Troisgros brothers — it is utterly perfect. If it were put down in front of me, I might cry. Now turn to page 103 and imagine the pleasure of crushing golden sugar threads into red currant sorbet. For all the bad boy rockstar in him, the cooking is modern French haute cuisine. Palladin expresses the same level of expertise, but his presentation embodies a new world verve. It's a mature, freer spirit at the plate. In 1989, when Cooking With The Seasons was released, Jean-Louis Palladin was 43. When White Heat was released in 1990, Marco Pierre White was twenty-nine — a pauper prodigy (read the foreword by Albert Roux). There's a fifteen-year age gap between the two. Palladin was born in 1946 in post-war France, in the early days of national recovery from horrific loss. White came into the world during the British Invasion — fed a diet high in Robert Plant and Mick Jagger. What they were doing was taking eyes off France. London was ascending, and America. A pivotal moment in global culinary history and culture. Besides these two, dozens of chefs leap to my mind. Too many to name in this small piece for fear I'd miss someone beloved. Those were the salad days of my apprenticeship. *** "You need to say to your wife, if you have a wife, 'I'm sorry, but you will need to be second in my life…Being in the restaurant 10, 12, 14 hours a day, that's your family." Jean-Louis Palladin The work family is a luxury of men. Think of how many lonely partners and kids — real families — there were (and probably still are). Men chased stars and young women and promoted their books and restaurants. Their spouses managed households and children. Not a real partnership. Stepping back for a woman's career was beyond our imaginations. True equity remains a radical concept for many chefs. White and Palladin were not easy men at work. There's the crying story about Gordon Ramsay at Harvey's. Eric Ripert said this about an almost early departure from The Watergate. "The performance of masculinity, and its conflation with genius, has not been a great thing for women, who are simultaneously the genius's victims and forever excluded from the club of genius." They behaved in a way no woman could. Like they owned everything. Women were doing brilliant things in restaurant kitchens — chefs like Barbara Tropp, Joyce Goldstein, Lydia Shire, Nancy Silverton, Alice Waters, and Sally Clarke. I staged in one of their kitchens and never looked back. Chasing heroes who looked like me was a choice. But the patriarchy was, and is, in me. Just like it's in you. Stripping away a dominant culture takes rigour and attention to detail. I’m wary of anyone professing enlightenment. We've been stingy in applying the luscious genius sauce to women. Like a filthy apron, it's a character flaw in our industry. It takes the smallest effort to speak of and treat professional women with high regard. "In the wake of #MeToo we began to undertake a collective thought experiment — or maybe it was just me — in which we tried to imagine a world where maleness, virility, license, and violence were not required to make great art." When do we arrive? *** When it was released, I heard The Blaze's Territory on a late-night CBC radio program. I could not stop listening. It always gets me out of my chair — longing for a packed, sweaty dance floor. The back and forth between machismo and family love is gorgeous. The scene where the four men wearing thoubs are kneeling on their prayer rugs as the sun sets over the rooftops of Algiers is gorgeous. And the way they crowd in to smoke the shisha. The Cannons is for twenty-seven-year-old me. 20172019This started as a story for Catapult. I signed a contract to write about No Meat Required and the process of creating a first book. I’d done an hour-long interview with Alicia Kennedy. Then the magazine folded. It freed me to write as I like — to be wildly biased. *** I was standing in the poetry section of a bookstore on a grey March day in the same week I’d received an ARC of No Meat Required. As I’m scanning the spines of the hyper-slim books, a thought drops — Alicia Kennedy has the same publisher as Jane Hirshfield, James Baldwin, Mary Oliver, and Colm Tóibín. Beacon Press, of fucking course. Stitching the connections together made me smile. “In college, I studied philosophy and read Marxist texts, including One-Dimensional Man,” Kennedy says, “I was really excited about having the same publisher as Herbert Marcuse.” Did you know she’s a total geek? *** “I was born in 1985. My mom made chicken cutlets and spaghetti. We didn’t even eat yogurt.” (Show me a better bio.) That’s the Long Island girl talking — fresh, relatable, calling in her audience. Born a few generations behind Moosewood and Diet for a Small Planet, she locates herself in mostly modern history. How she became a vegan is convoluted and Moby makes a guest appearance. She started a vegan bakery, wrote reviews for the Village Voice, and was a senior copywriter for New York magazine. “The book is cultural criticism, but it is like a love letter to this weird subculture that has given me so much,” she says. Her diet is anything but static. She won’t say no to oysters on the half-shell. Is the martini a trademark? Some of it challenges the evangelists. “When you have an alternative diet, people will think you’re coming at them with judgment. I started the process, hating the term plant-based eating, but I found it useful along the way. It’s a phrase that brings people in. We need to do whatever we can to make it more inviting.” *** Go to the back of the book — to Notes and the Bibliography. Alicia Kennedy reads. I marvel almost weekly at how she keeps it all straight for the newsletter — From the Desk of Alicia Kennedy. I’ve put books she’s mentioned on hold at the library. So have many of you. “I sold the book in June 2020 and imagined writing it in the Rose Main Reading Room at the New York Public Library, working with the world at my fingertips. If I needed anything, I’d talk with a librarian. But I wrote it during a pandemic in San Juan, Puerto Rico. There was no public library. I bought books, used Open Library a lot, and paid for an app to access academic papers,” she says, “I take handwritten notes while reading, which I often only return to when fact-checking. That process imprints the material on my brain in a different way.” She credits Jonathan Kauffman’s Hippie Food as a source of inspiration. Sarah Schulman is her favorite non-fiction writer. *** “I found the process of writing a book hard,” says Kennedy in the first five minutes of talking. Hearing it is a relief. And I'm curious. The plan was to write a chapter a month through to the deadline. But a year went by with no progress. Anxiety took root in the absence of work. The real fear and worry of living in a global pandemic didn’t help. And Kennedy was still busy, writing bi-weekly essays and building an audience. Advances for first books are not enough to stop working. Discovering the internal barrier was the diamond that came out of the months of inaction. Kennedy believed the book had to be wildly new and original and knock everyone’s socks off. “My career was on an upward swing, and I had this idea that this was my only chance to prove myself,” she says. Letting go of unrealistic expectations was a turning point. *** I tore through No Meat Required. I could not shake the feeling it will be big. It made me want what’s next. “The book feels like a closing chapter in a certain way for me,” she says. May she make good money and take all the time a second book demands. Her win is ours. No Meat Required is cultural history written by a bright mind. It’s punk rock with a homeopathic-sized dose of nostalgia. It’s modern Americana. Alicia, onward. Shoutout to your mom. You did good, girl. 🤟 *** Full disclosure: I attended a micro-conference in Brooklyn in 2018 — the Food Writer’s Workshop. The cotton bag still hangs in my closet. I can’t bear to send it to Value Village because the experience was pivotal. It’s proof I was there. Tickets, including lunch, were $13.50 U.S. It was affordable...inclusive...a space for me. The big food publishing events cost hundreds of dollars — a barrier for new voices. Alicia was an organizer, along with Layla Schlack and Emily Stephenson. The panels and discussion were rich — I took one photo the whole day. I made invaluable connections — met Lukas Volger, Korsha Wilson, Mayukh Sen, and Marissa Rothkopf. I spent four days in New York and stayed at the 92nd Street Y. My room was so cold I wore everything I brought in my carry-on to bed. All my extra pennies went into eating. Duh. I wasn’t thinking about that hardship sitting across from my friend Lauren at MeMe’s Diner. Priorities. This expresses some of the joy of that trip. *** The album Dynamo by Soda Stereo was what Alicia listened to a lot while writing No Meat Required. She shared a playlist from that period. I chose the song because, damn, that guitar intro! Turn it up. Disturb your neighbours. 2007 (1992)If I ever have a garden again, the first thing I'll plant is black currant shrubs. A glut of the berries in July is a blue-ribbon problem. I'd gather them in greying popular fruit baskets to make the Cassis Jelly recipe on page 231 of Saving the Season. According to a note on the page, I made it first on July 24, 2013 — a Wednesday. My muslin jelly bag is permanently stained an inky black purple like the colour of a new tattoo. The flavour of berries, citrus, and herbs is a palate stunner. It's got pucker. Spreading it thick on toasted sourdough with melting cultured butter is a pleasure. Eating it standing barefoot in dewy grass is even better. Cassis jelly is a country good morning. "Recipes need stories," writes Kevin West. Now you know why I like the book. It's made by a writer in no big hurry. To say it's about preserving is not the half of it. Like a Tennessee Waltz quilt, West stitches together recipes for Sunshine Pickles and Peach Jam with essays on a Shenandoah Valley road trip and the sensual vegetable portraits of Charles Jones. There are lines of poetry from Pablo Neruda, "I want to do with you what spring does with the cherry trees." On almost every page, there's a new seduction. "Lemon verbena and sweet wine in the first variation provide weightless layers of flavor, akin to the translucent atmospherics in a Turner painting," he writes about Apricot Jam with Honey and Lemon Verbena. Threading a homely craft to a master painter is the work of a writer who embraces culture with warmth and generosity. The headnotes are like cocktails before dinner, with nice snacks. A space to build appetite and nurture a connection with the reader-cook. West delivers technique with a side of charm. In the intro for Zucchini Dill Spears, he recalls something his mom said about growing zucchini that will bring a smile to a gardener's face. "After you pick a plant clean and walk away, you can glance back over your shoulder and see new ones that already need picking." Any opportunity to tie the kitchen to the garden is seized. "We are saving, even in our urban kitchens, a sense of the agricultural cycle," he writes in an essay on Edna Lewis. There's a photo of seven-year-old West holding a flat of sun-warm crimson strawberries on page 52. Smiling for his mom behind the camera. The two of them just back from picking. He's a wholesome vision of childhood in worn jean coveralls and no shirt. I go to the book mostly for jam, jelly, and marmalade. My passion. Because it's made without commercial pectin. I like the challenge. The cook must consider the season's imprint on the fruit's fragrance and taste. Or, as West says plainly, "Getting it right each time is different." Maybe it's owing to his Southern roots, but West excels at making introductions. We meet June Taylor, a jam-maker he calls an "archeologist of pre-industrial country life." To get a sense of her obsession, Taylor labels her preserves according to fruit varietal. And another California jam-maker, Robert Lambert, says, "I don't want to run a business…I want to make stuff." (If there was ever a mantra for my working life, that's it.) If you need to ask how much their jam costs, you don't know a stick about what goes into making it this way. But for the record, it's a lot and not near enough. West and his friends "put up" in small batches. This is not your family's all-day-by-the-bushel-canning-bonanza. Those days are mostly past. But the photo of Ada Mae Houston's root cellar on page 421 will stir nostalgia for that home-grown abundance. The cookbook's been open on my kitchen table while Mason jars made a racket in a boiling water bath, and a trail of sweat ran down the small of my back. And I've sat and read it for the learning. There's joy in it, and not just for the cook. We're friends if it's in your collection. There are homespun innovations. West suggests lining the bottom of a water bath with ring lids instead of a rack to raise the jars off the direct heat. And he fills a Ziploc bag with brine to use as a weight for a crock of dill pickles in case it springs a leak. West would be eyeing the ring-bound books in your grandmother's kitchen for inspiration. Mrs. Dorsey Brown's Green Tomato Pickle is a church-lady recipe from a St. Thomas parish cookbook near Baltimore. And the Orgeat, or sweet almond milk, has roots in a 19th-century cookbook, The Kentucky Housewife by Lettice Bryan. Last week I added more 'to-make' tabs for Cherry Preserves with Red Currants and Piquant Pears with Bay Leaf and Black Pepper. The book is crafted with Stahl house care. Modern Americana with its heart in California. I could take it from the preserving section and squeeze it between Zuni and Chez Panisse Cooking on the shelf. Where it sits in my heart. West wrote the book in the Hollywood Hills in a place called Greenvalley. Take me there. West writes about a friend's cookbooks: "What distinguishes Ziedrich's two Joys are the intangible qualities of ambition and authority, traits common to all enduring cookbooks." An apt counter-narrative for much in our high-speed machine-made world. Clear through to the end, he delivers. The Epilogue is a solid reference section. My three-word blurb: — endearing and enduring. Saving the Season is a book to pass through generations. *** The brilliant pop-art strawberry is from Jay Heins at Numen Communications. He's art directing on the cookbook posts. What a relief to focus on the words. And to collaborate with a talented, creative human. Less is more for me these days. I'll be posting every two or three weeks about a cookbook. *** I went back and forth on the music. Settled on the new and the old. I could serve Steve Winwood in so many ways — the Spencer Davis Group, Traffic — but I chose Blind Faith. An extraordinary musician right from the start. © strawberry by eva.yuna via Freepik. 20231969 |

Archives

July 2024

© Deborah Reid, 2021 - 2024. All Rights Reserved. Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed