|

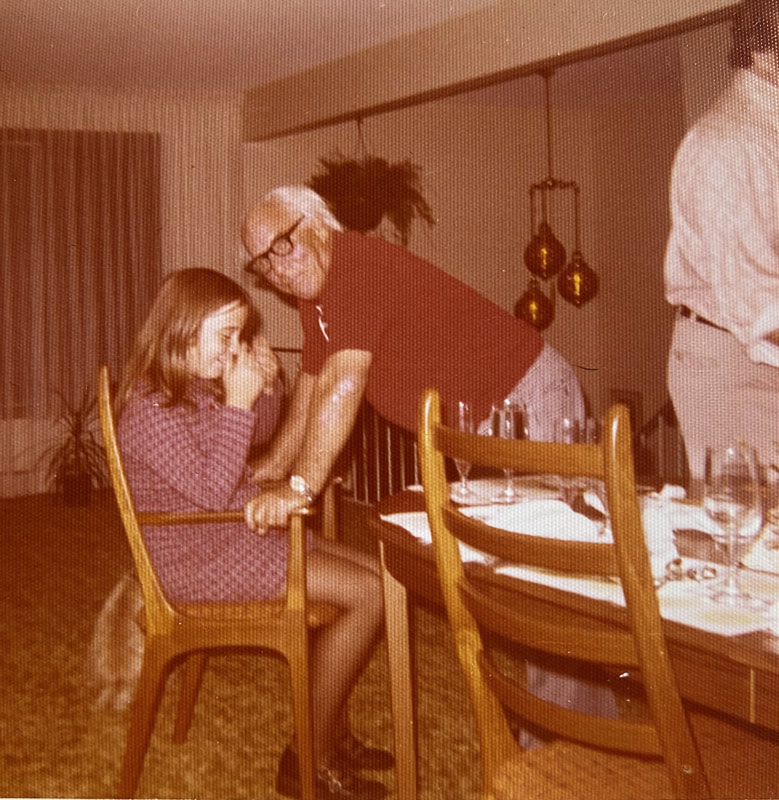

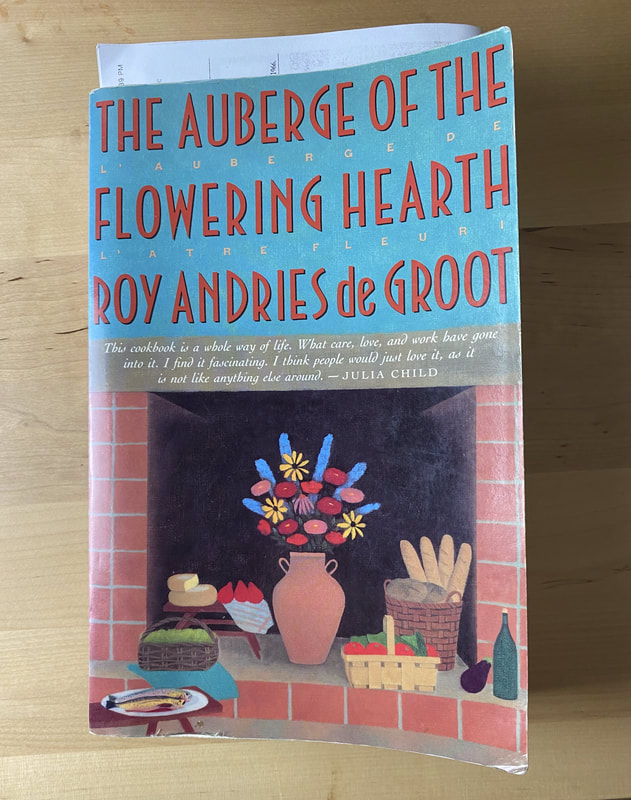

I saw Roadrunner on Friday, July 16. In a theatre. I've been struggling with ideas and words since. Then this came thundering in. *** I wish I could tell you I read a lot of good student book reviews on Kitchen Confidential. I did not. The exuberance was there. But the scale of grading made it a slog. It would have embarrassed Anthony Bourdain how many writers he squeezed out of young hands—Jim Harrison, Calvin Trillin, A. J. Liebling. Fuck. I try to imagine him reading William S. Burroughs for the first time. Or Joan Didion. I knew the book was important by how many hands it was in. How many young people wanted to talk about it. I rolled my eyes on occasion. Bromance. *** Reading a writer can be tricky. Sometimes we can only see one thing. Even when there's more. And it's rich. Anthony Bourdain broke it open for cooks. Not singularly. I'm mindful of white macho bullshit. Lionizing men who were humans. He was an intellect, a strange bird, in our midst. *** Trading his knife for a typewriter after work. Talking with and about us. By the yellow light of a desk lamp at night—dust flecks whirling in the aura. Or by daylight at the kitchen table. A pack and a half of butts in the ashtray. A lanky, mercurial young New Yorker with grey matter, charm, and ambition. *** Bourdain turned a blinding flashlight beam on some of our darkness. We thought the whole thing was a compliment. Treated it like a permission slip. When some—maybe all—of his aim was to write black comedy. Stay sane. Earn a living on words. Tell damn good stories. *** What was good? The follow-up. Medium Raw. His "bloody valentine." It's where he corrected course. Put a tie on. Look at the cover. "To Ottavia." A thoughtful, bright work in her honour. He had a spine. Confidence. Did the job of cleaning up. Shared the lessons. Took ownership. Fuck, that's attractive in a man. If you haven't read it, you're missing something. *** We were proud. Wanted to be near him. Or our version of him. I saw him at Massey Hall. September 22, 2010. He held the stage. Like some of us, he didn't know when to slow down. Or stop. One setting. Fast forward. Some of the world starting to flash by the window of a shiny black town car. Mixed with periods out on the edges of the earth. *** Look for his reading lists' online. There's a stuck-inside winter project. Pile the books he read and loved on your bedside table. Work your way through them. A way to remember. A fine tribute. *** This morning on Twitter, a man wrote a painful message marking his dad's death at 56 from alcoholism. Bottoms start way before the end. They need a long runway to get up to full speed. There are so many witnesses. And tender humans getting hurt. *** He was an addict. Roadrunner was terrible at addressing that cold hard fact. It's tabloid. Bourdain was responsible for his life. Morgan Neville did not make that film. Instead he was a vulture at a smoking funeral pyre. That's my review. I'm not writing for the New Yorker. *** We're consuming Bourdain still—like co-dependents. Remember Elizabeth Shue? Her performance in Leaving Las Vegas? She was nominated for an Oscar, Best Actress. For playing Sera. Her character is us. Right now. All I can hope is that all profits are going to a higher good. *** His brilliant sparkling mind. His singular voice. *** I'd love to re-grade a bunch of those book reviews. I've changed. For the better. I'll wait for someone to write Bourdain's life. Real and good. I know it will come. There's just the waiting. 19771988/89. Tuesday through Saturday nights in garde manger and pastry. The best French restaurant in the city. On Queen Street in the gritty before-times. Joanne Kates swooning in The Globe and Mail. Like Rundles, I always seemed to land in kitchens at the top of their game. A mix of luck and ambition. This image was on a postcard circulating in the restaurant. *** Claude was from Brittany. There was a poissonier on the line. Beautiful ingredients flown in from France—samphire, morels, Fine de Claire oysters. Coquilles Saint Jacques à la nage and white asparagus with a silver boat of Sauce Bearnaise. Fraisier cake, marjolaine, and tarte fines aux pommes. Sigh. *** Killing lobsters in the back prep area. Images of big breasted, half-naked women on the wall behind me. Air-brushed lips and curves and Farrah Fawcett hair. Kitchen supply and auto body shop calendars. One Saturday night, during a busy second service, a chef and waiter got into a fistfight in front of my station. Lunging and throwing punches. French porcelain clattering. Men scrambling to damage control. Pressed up against the wall in my corner, shucking oysters. Laughing about it later in the Beverly Tavern. That's how it was. Normal. And not all the time. *** There was a dangerous chef de partie. I did not feel safe. For good reasons. Who would I tell? *** Claude told me once I drank too much. I had some thoughts about him too. Women moved out, not up—dishwasher, prep, pastry and appetizers. Vanna White sweeping her arm toward the promised land. The night before I finished my notice, after training a replacement for a week, Claude set his sights on tearing the guy down. My heart sinking watching him walk out the back door mid-service. Just about free. Then Claude turned on me. Jabbed his finger in my direction and told me I wasn't done until he said so. Men expecting women to clean up after them. Be obedient. I had training in that already. Fuck that. Took my knives home. The phone rang for a long time the next day. *** Ten years later, I ran into Claude on Queen Street. Told him he was right about the drinking. He admitted being miserable. We caught up for a bit and then parted. It was good. *** I played my part. Misery finds company. Fierceness was sometimes my armour. Not always. Found a place where I could wear it. I can say that openly because I know I am not alone. Been trying to have more real conversations. Without expectations. Not all of them end so neatly. Me and Claude were ready. The point is I'm open. *** All I wanted was to cook. It felt like home. The circle of fucking life. *** A man playing the piano can make me sweet. I loved this album. Walk on. 1988It's hard not to sound pretentious about some things in my food life. These are actual events, and this is how I stitch them together. I count my blessings. *** When people working in food media and the chef crowd go out to a restaurant, this can happen. Someone says, 'let's order everything on the menu,' or a restaurateur will say, 'we'll take care of you.' It's often a cue to prepare for more food than you're into. And it can go on. Sometimes I'm up to it. More often, I'm not. *** At Frenchette, in New York, I had three courses. My companions took the other road. The cooking was sublime, but my world came to a tire-smoking stop when this Tarte Tatin was set in front of me. I can't look at that dimly-lit picture without gasping a little. Pastry talent in the kitchen. My heart beating. Loud. We're seated in a banquette, and I was concentrating—not like exam-level—because French cooking is what I trained in. I have expertise. All my senses open. Sometimes I want to get to know a restaurant quietly. Have space to give the food and room thought and attention. Remain alert to the subtleties. Be good company. Too much food on the table in any restaurant, and the thread starts unravelling for me. Too much time at a table can mess with the business too. FOH staff wondering when they can go home already. What if that Tarte Tatin was set in front of me after ten courses? The gasp might have been different. *** I ate at Restaurant Pic the year Anne-Sophie won three stars. The thrill of that journey—an abundance of wonder and thankfulness. Unnerving too. It was 2007. The event put an end to a fifty-year blackout for women working in French restaurant kitchens. The shoulders she stood on. The red Guide Michelins in the foyer. Walking past the open kitchen. Everyone at the table wanted the tasting menu. I had to play. Those are the rules. Timing and all. What I remember most is how little I remember. There were so many astonishing courses and gorgeous wines for my companions. At some point my capacity to take it in froze. *** I took notes at Saturday night dinner at Milkweed Inn. Who doesn't want to record the details, scribbling like a poet or anthropologist, when you're eating Iliana's food. I can flip to the pages in my notebook when my spirit needs an infusion of beauty and hope. It's a peaceful and quiet place. The company that night was so fun. Dandelion yellow light seeping from windows into a squid-ink sky. Stars sparkling. Laughter a thread in the wild night noises. *** Long menus can feel overwhelming. Sometimes tiring. Sitting in a restaurant for hours can be torture. Sometimes I do not want to be dipped in hot butter. Give me three or four beautiful things, please. *** Signs of love and welcome from friends in the kitchen are nice. Never expected. Make it amuse-sized—pre-dessert, and I'm ecstatic. Maybe this is me getting older. I don't need the gesture. But if it happens, make it small and place it well. It lands deeper that way. *** I'm currently gorging on this man's music. *wink* 2020That’s Harry, my grandfather. He loved me. I knew it. He was chief engineer on lake boats—the E.B. Barber for a long time. Time with him was an adventure. Spending the day on the Welland Canal. Boarding as the boat came level with the lock. Theo picking us up down the way. A cook baked us a chocolate cake. I can still see it in the 9 x 13-inch aluminum pan—polished chocolate buttercream piped in a wave pattern. We made the first cut. Food’s a big deal on the lakes. Harry was easygoing and affable. I never saw him angry. To me, he was a peaceful harbour. He could hold his own too. Boats attract transient labour—there were some dangerous characters below deck. I’ve heard a few good stories. Not that long ago Peter, my uncle, told me a hair-raising story about Harry that took place in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. We shared a few moments of shock. And then gratitude. *** We spent Christmas one year on a boat in Midland my grandparents were babysitting. They used to do that in Montreal too. Theo in the galley kitchen. Me and my brother on the run. Remember when parents didn’t know where you were for a whole fucking afternoon? On a lake boat? Two memories: When a boat’s in ballast, it sits high in the water. Ten-year-old me climbing a rickety aluminum ladder in deep December, looking way down at the ribbon of black slushy water between the boat and the dock. Harry in the other direction holding his arms open. Me and my brother drinking the tap water—straight from the lake. Not Potable Water. Who knew what that meant? The size of Harry’s eyes when he found out. Nothing happened. *** Harry could never walk past a bakery. That memory and the thought of holding his callused hand melts my heart tonight. Sausage rolls for him. We could have anything. I was that weird, nerdy food kid from before I can remember. Napoleon slices—custard and puff pastry—I liked them best. The chocolate-vanilla glaze was magic. Remember the wonder when you learned how to do that as a young apprentice? By the time we left, everyone behind the counter had fallen for him—his thick Scottish brogue and natural charm used to good effect. I was in that golden glow with him Harry gave freely. No strings attached. *** I spent the night listening to Nathaniel Rateliff. I can’t believe he’s new to me. Where have I been? This song! 2015If you know, you know. Arrived on Monday, April 18, 1994. The day of the Boston Marathon. I thought I’d get to hang out with the crowds watching. Went to Biba to say hello first. It was fucking busy. Straight into my whites. A good introduction all around. Most of what I knew at that point was French. Lydia was travelling everywhere and eating, and her flavours and palate left me speechless. The restaurant was on fire. So was she. Along with Susan Regis, they made a great kitchen team. No cooks were in the kitchen when Johnson & Wales called—that was amusing. A novel response to the realities of student loans. New things to cook and eat every day. Making Mexican chorizo, rolling trofie pasta for tripe, sobrebarriga en salsa criolla, a Columbian braised brisket dish that defied what I knew as delicious up to that point, brains in beer batter, salads with purslane and chicory. Thirty-two years later, I still cook things I learned there. So do friends in Stratford. Never went back to staging with men. Female leaders were where it was at. Boston in the spring is pretty—flowering trees, green parks, and the Charles River. Spent one day in the Schlesinger Library. Want to return for more. Arancini in the North End. The experience was everything I hoped for. *** The natural choice for music was Aerosmith. But the association with this song is stronger—the Stone Temple Pilots remake of the greatest Led Zeppelin song of all time. Fight me. :) 1994August and movies seem to go together. One of the ways I’ve been caring for myself—watching a movie at night. Undistracted. Hand’s free of phone or hobby. Just watching. The French Connection has not aged well. The racism is painful. I turned it off. Portrait of a Lady on Fire. Like looking at a painting. Steamy. Cinema Paradiso. I’ll watch it forever—the feeling of warmth in my heart. Like Moonstruck. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve seen it. Its beauty is never lost on me. Olympia Dukakis. A master. The kitchen table. The New York cabs. The way Ronny wants Loretta. Put that on repeat. *** In the before times, I went to a matinee most Friday afternoons. On my own or with a friend. The best is being in a theatre—TIFF or the Varsity. I like it when I can reserve seats. People talk about the cost. It’s one of my drugs of choice with a side of popcorn. Maybe this is the fall and winter I take a film course or join a film club. Talking about great movies after. That stuff’s magic dust. John Birdsall scored a copy of the “Auberge of the Flowering Hearth” by Roy Andries de Groot at a thrift store. Posted it to Instagram. Here I am. It’s one of the books I’m scouring your shelves for—if you have it, I trust you more. Weird, huh?! The book inspired a trip for me into the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes. The inn was my first stop, but the monastery at Chartreuse and visiting Annecy were right behind it. I drove a car out of Lyon, and because it’s a bit nerve-wracking at first—doing it in another country—I was on alert. I tuned into a classical channel. It was early on a near fall day. The sky was matte grey, and a light rain fell. The station was playing the Brandenburg concertos and the weather, the forests at the base of the French Alps, and the music felt coordinated. The roads were secondary, and only a few people tailed me. Colours were vivid—green fir trees, glistening black bark, wet terra cotta earth, and fallen wood in streams decaying to charcoal, rust, and yellow splinters. I overshot the road to the inn twice. Third time got lucky. It was a single lane and modestly steep. Dairy cattle grazing in the field to my right. They wore bells. I turned the radio off because the clanging was gorgeous. They chewed and observed me. I knocked at the door. Here it was mid-September—summer tourists gone and a window of reprieve before ski season. Maybe the Tour de France had gone through that summer. My years of seasonal employment made me feel sympathy for the owner. I was quiet and thoughtful. He gestured me into the foyer. I did not expect it. Took a picture of the side of the building before I left. A lovely day in photos gone to the great unknown. Maybe it’s why I can recall it in detail. De Groot wrote the book on visits between 1962 to 1967. Here is his opening sentence in the 1982 preface: “It is now fifteen years since I first approached the forbidden granite wall of rock, found the jagged cleft cut by the rushing torrent of the river, negotiated the narrow road on the ledge above the ravine, swung around the hairpin bends and plunged through one rock tunnel after another, until I found myself in the sun-splashed forest, surrounded it seemed, by an orchestra of a thousand birds singing in harmony a hundred songs.” Who would not want to go there? *** The rain stopped. I found a small hut serving food—eating an escarole salad with goat cheese and bread and butter on a two-table patio—sheep grazing in the pasture on the other side of the driveway. Lone tourist mainly owing to the weather. The sun broke. Paragliders hung high overhead in warm winds. Sails in primary colours. Why is a sight like that so good? *** In chapter two, de Groot gives a brief history of how the carthusian monks at le grande chartreuse came to settle there. It was easy to see the landscape through his eyes. Its character is essential. I’ve cooked a few things like le gratin Savoyard and la salade de pissenlit aux lardons from it. I like the stories. I’ve come this far without saying a word about the hosts—mademoiselle Ray and mademoiselle Vivette. A gracious couple with complementary skills in the kitchen and dining room. It was a place where de Groot felt comfortable, alive even. Because of its size, a stay required some level of intimacy with the daily rhythms. I’m cutting myself off there. Read it if you like. *** I ended the day in Annecy. Sunday lunch was tartiflette at Le Freti alongside local families and tourists. I had no appetite left for it but wanted to taste the fondue and raclette too. Then there was a one-of-a-kind lesson in humility in an underground parking lot. I believe a few more people than me have found themselves in a similar predicament. Sheepishly telling strangers, I’d blocked the automated exit. Kind people helped me sort it. *** Travelling to places accompanied is good. But sometimes it's perfect going alone to places important to me. 2009This is about childhood violence. Please, take care of yourself. *** I always associated blackouts with drinking. I'd have too many beers, and my inner monitor went blank. It's one of the ways I knew I had a problem. I didn't drink like most of my friends. Jeanette told me that when I was seventeen. A long time ago, I got help. Thankfully it stuck. Two cute kids. That's how my brother and I looked to the outside world. People used to compliment my parents on how well-behaved we were. They didn't know that being good was how we stayed safe. Chuck was 6'2" and weighed between 250 and 375 lbs. He was a big man. But the first time I remember blacking out was around age six or seven—in 1969 or 1970. I'd gone to the store to get something for him. Crossed a four-lane road in Burlington by myself. Those were the days. Something tempted me at the cash, and I spent a quarter on myself. Was it a lot of money then? When I got home and my father found out, things got crazy. His rage was scary and unpredictable. He let himself go to dark places. Insanity is what I call it now. After he beat me, he did the unthinkable. I was terrified of the dark. He dragged me up the stairs to the bathroom, threw me in it, closed the door, and turned off the light. Everything goes blank. Around the same time, my brother and I are playing on a swing set in a campground across from our apartment. I saw my father in the distance coming towards us. I think I peed myself. I could tell by his gait what was coming. I don't remember what we had done. The thing about violence is it distorts all infractions. Nothing is minor. Everything is worth hurting over. The threat of it is omnipresent—its scent is in the furniture and the baseboards. The line we walked as kids was frightening and narrow. Getting it just right took so much of my childhood. On that day, my dad had gone to the crock that held kitchen tools. He chose a slotted spoon. It was swinging by his side as he came toward us. As an adult, I've wondered about the progression of instruments—from wooden to metal spoon. There had to have been a moment of thought about it. The kids playing with us backed away to a safe distance. They watched while my father wildly grabbed at us. I was trying to swing myself away from him while in his grasp. To soften the blows, I put my hand up and felt the pain of it connecting. He dragged us away. Out of sight. Behind the curtains of our lovely home. Everything goes blank. One of the hardest things I've had to recover from is childhood violence. I think there's an ancient vein of it in my family. No one wants me to talk about it. One of the side effects of doing it is isolation from relatives. Blackouts protected me from the pain. The unbearable feeling of being wrong to the core, of never, ever living up to expectation. Of feeling unloved. My dad made a blanket apology once. There might have been a scotch at hand. He never talked about it in detail. Didn't want to hear about it from us. I rode that out for a while. Then when I was 49, I confronted him about another incident. I did it under good guidance—had rehearsed it with a therapist. Had a support network behind me. I was fucking scared. It's the bravest thing I've ever done. And I've done some brave stuff. Because we were in public, he seemed to handle it okay. But the next day, at the dinner table, he exploded. Behind the curtains in his lovely home. I left. Our relationship changed. He built higher walls. I've been trying every way I know how to tear mine down. Getting softer is my mission now. *** I held my breath the first time I read "Breakfast at McGee" in Kate Christensen's Blue Plate Special. I could not believe it. I was not alone. *** It was hard to choose a song, but this felt right for where I'm at. After writing this piece I bought myself dahlias and ate a couple of oatmeal raisin cookies in the park. Today I'm in my kitchen cooking beautiful food. I sent messages out to friends. My phone dinged for a while last night. Good people sending me love. 1998A little-known fact about me. I wanted to be a potter. At twenty, I applied for undergraduate studies at Trent University and the Craft and Design program at Sheridan College. At that age, the way forward wasn't clear. Both accepted me—a trusted elder helped me chose the former. I have zero regrets about the path I took. The beauty of time is seeing my interests and expertise weave together in unique and astonishing ways. I told anxious students not to worry about picking a career until their mid-twenties. Explore all possibilities was my best advice. I didn't step into a French kitchen until I was 25. In my first meeting with Jim Morris at the Stratford Chef School, he told me I was too old for the profession. He was wrong. I had the pleasure of proving it in his restaurant. *** I took a pottery course at the Dundas School of Art and enjoyed it. It may someday become a serious hobby. I follow a lot of potters on Instagram and share their work in my stories. Some of you may have noticed. I have beautiful pieces—a few of them from my father. This bowl is by Kayo O'Young, a Canadian porcelain master. I can't believe my cat hasn't broken it, yet. *** If I were a potter, my work would be beautiful, just like my cooking and writing. I have an artist's heart. I still have hopes and dreams that are precious as porcelain. They're mine to nurture. *** Billie Eilish's sultry vocals are everything I want to listen to right now. Happier Than Ever. 2021 |

Archives

July 2024

© Deborah Reid, 2021 - 2024. All Rights Reserved. Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed