|

I began my cooking career in fine French restaurants in the mid-80s when the revolutionary ideas and techniques of France's Nouvelle Cuisine were trickling down into Canadian kitchens. One of the most significant changes involved cooking vegetables—green ones in particular—for less time to retain their vibrant colour and pleasing texture. Anyone overcooking vegetables, so all their natural appeal was discarded with the cooking water, was thought déclassé. (Exemptions were made for grandmothers. Who dared to tell them times had changed?)

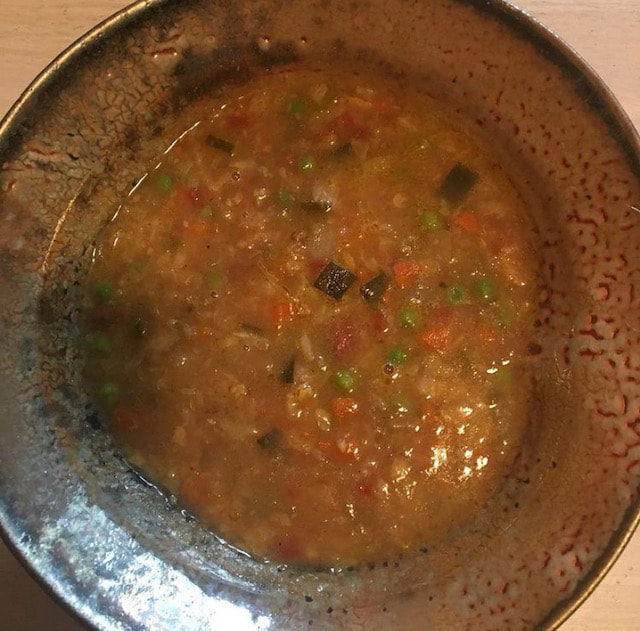

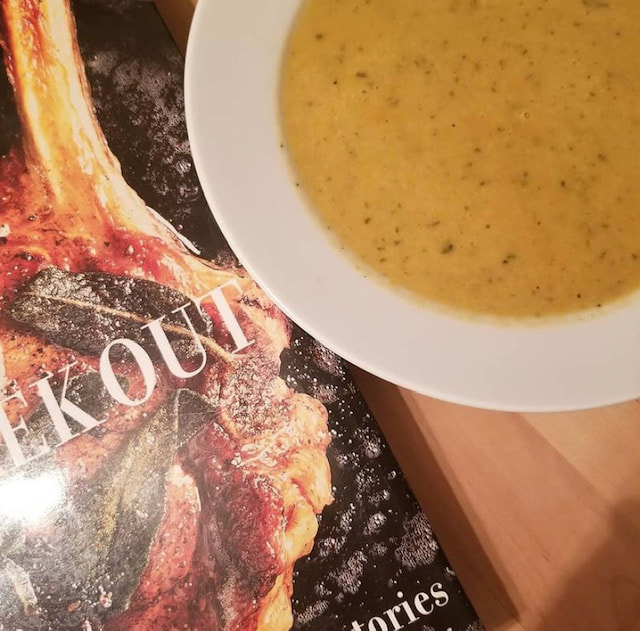

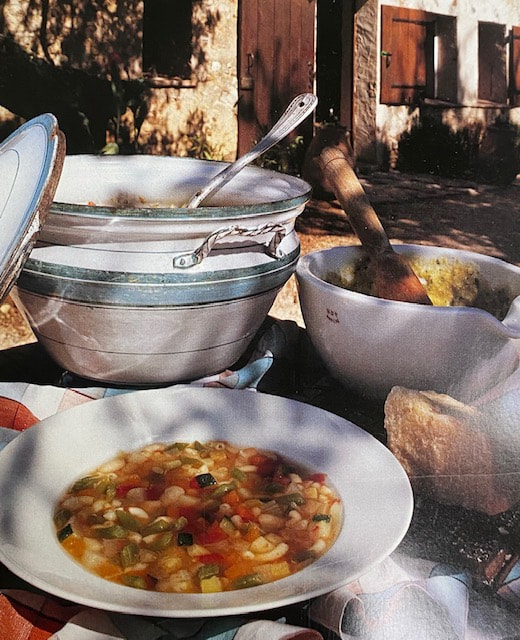

Cooking vegetables perfectly requires skill. It's as disconcerting to crunch into a vegetable more raw than cooked as it is to eat those killed through overexposure to heat. When a fork or knife can't penetrate, things get messy and carrots or broccoli shoot like missiles across the table. But there are times when vegetables are best cooked to completely tender. There's an essential pleasure in simmering or stewing them well beyond reason to a rich vegetal concentrate. Often the French call these dishes paysanne to signal their deep agrarian roots. Three vegetable soups deliver this kind of simple enjoyment to me. They're not the vibrant green or exotically spiced purées of celebrity chefs. They're made with little more than fresh vegetables, good stock, salt, and pepper to season. The first is Marcella Hazan's Minestrone di Romagna. I cooked it the day she passed, as a tribute. A mixture of hardy roots and tender green vegetables are simmered over low heat for three hours. Miraculously most of them retain their shape while hovering perilously close to the edge of deterioration—at the end of cooking discernible cubes of potato and zucchini, remain along with the green beans. The vegetables that meld into the soup are the sliced caramelized onions, the first in the pot, and the shredded Savoy cabbage, the final addition. They add sweetness and form a tender, soft mush, the soup's underbelly. It's the kind of humble, nourishing meal found in the farmer's bowl in the painting, Il Mangiafagioli (The Bean Eater) by Annibale Carracci. Marcella writes the soup, "has a mellow dense flavour that recalls no vegetable in particular but all of them at once."[1] Her descriptor perfectly suits another soup I adore from a book no discerning cook should be without, Simon Hopkinson's "Week In, Week Out." His Simple Cream of Vegetable Soup is on the menu of my last meal. When fully cooked and puréed its colour falls between harvest gold and avocado green, the quintessential 70s palette. Two bunches of fresh watercress bleed their spring brilliance after an hour of cooking. Hopkinson claims to have learned how to prepare this soup, "as a keen young apprentice at The Normandie, the renowned French restaurant near Bury, Lancashire when I toiled there during a couple of school holidays in the 1970s." [2] It tastes sweet and earthy from the leeks, carrots, mushrooms and watercress, and the slushy texture owes everything to the food mill, not the blender. Given its Normandy roots, the lavish whip cream finish is no surprise. It harkens to another time—of wonderful dinners in French bistros and chefs who cling with fierce pride to the dishes of their youth. The final vegetable soup comes from "The Roux Brothers French Country Cooking." They were a seminal influence during my apprenticeship. I met Michel Roux once, and when I asked him to sign this book (now sadly out of print), he beamed and told me it was his favourite because most of the recipes were his mother's. His eyes were sparkling. Their recipe for Soupe au Pistou has the same Gallic charm. It stands head and shoulders above all other versions. Over time, I have made a few small revisions—I use homemade chicken stock instead of water and cook the pasta separately. The cooking time here is the shortest of the three vegetable soups, so the broth remains crystalline. A final flourish of thick pesto stirred in just before leaving the kitchen is a triumph. It arrives at the table along in an ethereal herbaceous cloud that envelops the eater. I put it on the lunch menu at The Old Prune in Stratford, Ont., and customers waxed poetic about it (and about the goat cheese soufflé from chef Sally Clarke). If there were little in my culinary repertoire besides these three vegetable soups, I'd still be considered a damn fine cook. They're old fashioned, elegant and accomplished and need little else—a good loaf of bread, some fine butter, a piece of ripe cheese, and seasonal fruit to finish. Much is made of modern chefs planting gardens and turning to vegetables as a primary source of inspiration. They all want to be seen with their Blundstones sinking into the dark, loamy earth—a revolution, a modern innovation, like nothing we've seen before. In its subtleties, it could well be. But when I look into a bowl of one of these soups, I see the roots. Where vegetables are concerned, everything old is new again. [1] Hazan, Marcella. The Classic Italian Cookbook. (New York: Ballantine Books, 1973), p. 63 [2] Hopkinson, Simon. Week In. Week Out. (London: Quadrille Publishing, 2007), p. 229 Comments are closed.

|

Archives

May 2021

© Deborah Reid, 2012 - 2024. All Rights Reserved. Categories

All

|