|

I'm up today at 6 a.m., and early rising is not me. I love the night and fit easily into the rhythms of the restaurant business. Working until midnight, falling into bed at two or three in the morning and sleeping until after eleven is heaven.

I recall a time not so long ago when I slept like a babe in arms. Sleep's a new frontier for this woman at mid-life. I've decided it's futile to rail against this current state and try to accept it. So I'm up and writing at daybreak, an hour some writers proclaim the most creative. Do my nocturnal leanings disqualify me from this profession? There's a magnet on my fridge that reads: "Only dull people are brilliant at breakfast." God bless Oscar Wilde. The restlessness I'm feeling is more pervasive than just this one night. It's an energy shot through late winter when all northern dwellers grow weary of the snow and cold. My landlord switched from salt to sand for roughing the surface of the slick ice outside my door. The grey-brown on my walkway seems to sum it all up. Dirty pools of sand and snow melt to a muddy slurry on the white tiles in my foyer—how I long to wash it all away. I rushed outside into brilliant sunshine two days ago, walking directly into its warming rays. The light buoyed my flagging spirit and, for a moment, made an early end to this season seem within reach. The temperature rise softened the snow and ice underfoot making it crumble like shortbread as I walked. Out on the street in Bloor West Village, people unzipped their jackets and were soon carrying woollen hats and gloves in hand. I've been thinking about my bike and warm night rides in the streets between my house and the Humber River. I've put my name on a waiting list for a garden allotment in High Park but won't know until April if I'll plunge my hands into the earth. I push down the desire to purchase dahlia tubers with wild abandon, imagining myself sitting in the shadow of their tall, stocky, multi-coloured flower heads in late summer. I'm stuck between the oppression of this endless winter and the too-far-off promise of spring. This cold season can't pass quickly enough for me. March surely must bring relief. The sun will hang high in the sky long enough to trigger epic melts. Snowbanks will begin to recede, exposing a dirty and dormant terrain. My restlessness finds temporary relief in marmalade making. I've pulled from my shelf a book whose title, Saving the Season, makes me chuckle. I like marmalade, and it was the appearance in my local store of Seville oranges—with their distinct skin like cellulite on ageing dames—that reminded me of this kitchen pleasure. I have a great recipe from Sally Clarke, one of Britain's best cooks, using this prized citrus fruit from Spain. But the truth is, orange marmalade is not my favourite. I prefer lemon and, when marmalade of my own making is in short supply, I buy Robertson's Silver Shred. There's something less bitter, more acidic and fresh in preserves made with lemon. I have a recipe for a quick marmalade using Meyer lemons. I love their sweet-tart flavour and their skin is thin and tender and suited to a quick-cooking preserve. I can imagine the marmalade's orange translucence with bits of soft, saturated citrus fruit suspended in it. I've also settled on making something new: Fine-Shred Lime and Ginger Marmalade from Kevin West's extraordinary book.[1] It's a three-day process, just the kind of project that will chip a few more grey flannel days off the season. I learn from West the spongy white pectin-rich pith that cushions the delicate inner fruit is called the albedo.[2] There's something in the tumble of language he uses to describe the results that rally my enthusiasm, making my mouth water in anticipation. This marmalade, he writes, is "a translucent mass suspending a tumult of finely shredded green peels—and the powerful flavours of raw lime and ginger become elegant through dilution."[3] It's a preserve tinged the delicate green of spring hope. There's a Marmalade Cake I want to try, imagining spectacular results using lime preserves instead of orange. I know marmalade making is the right task for today. It will ease my weariness and leave me with the impression of productivity. I'm going to set out in search of the ingredients after another cup of coffee. The city has issued an extreme cold weather alert (too many of those this year to track). There's a storm bearing down on Toronto that's promising to wreak havoc on our already frazzled systems. Today I'll gather fruit from far-off sunny places and shake my wooden spoon at this fierce season. Winter be damned! On the horizon, there's the promise of sweeter, brighter, fresher things in my kitchen. [1] Kevin West, Saving the Season (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013) 477. [2] Ibid. 477 [3] Ibid. 477 I began my cooking career in fine French restaurants in the mid-80s when the revolutionary ideas and techniques of France's Nouvelle Cuisine were trickling down into Canadian kitchens. One of the most significant changes involved cooking vegetables—green ones in particular—for less time to retain their vibrant colour and pleasing texture. Anyone overcooking vegetables, so all their natural appeal was discarded with the cooking water, was thought déclassé. (Exemptions were made for grandmothers. Who dared to tell them times had changed?)

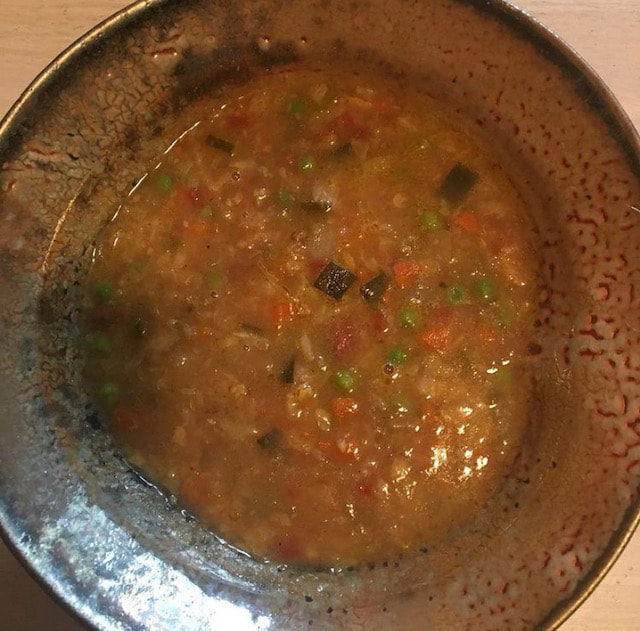

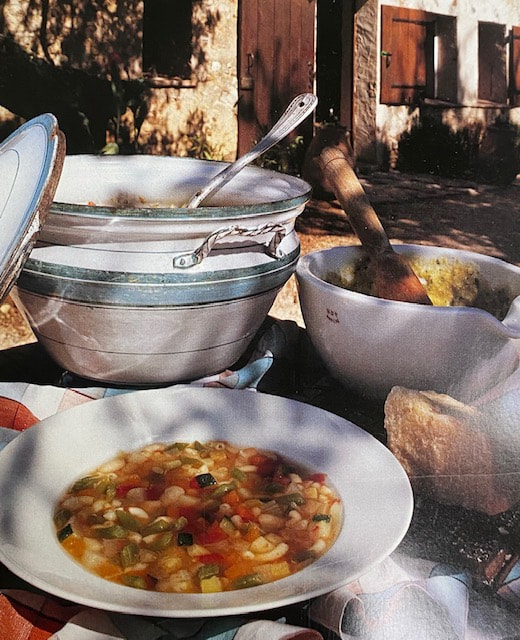

Cooking vegetables perfectly requires skill. It's as disconcerting to crunch into a vegetable more raw than cooked as it is to eat those killed through overexposure to heat. When a fork or knife can't penetrate, things get messy and carrots or broccoli shoot like missiles across the table. But there are times when vegetables are best cooked to completely tender. There's an essential pleasure in simmering or stewing them well beyond reason to a rich vegetal concentrate. Often the French call these dishes paysanne to signal their deep agrarian roots. Three vegetable soups deliver this kind of simple enjoyment to me. They're not the vibrant green or exotically spiced purées of celebrity chefs. They're made with little more than fresh vegetables, good stock, salt, and pepper to season. The first is Marcella Hazan's Minestrone di Romagna. I cooked it the day she passed, as a tribute. A mixture of hardy roots and tender green vegetables are simmered over low heat for three hours. Miraculously most of them retain their shape while hovering perilously close to the edge of deterioration—at the end of cooking discernible cubes of potato and zucchini, remain along with the green beans. The vegetables that meld into the soup are the sliced caramelized onions, the first in the pot, and the shredded Savoy cabbage, the final addition. They add sweetness and form a tender, soft mush, the soup's underbelly. It's the kind of humble, nourishing meal found in the farmer's bowl in the painting, Il Mangiafagioli (The Bean Eater) by Annibale Carracci. Marcella writes the soup, "has a mellow dense flavour that recalls no vegetable in particular but all of them at once."[1] Her descriptor perfectly suits another soup I adore from a book no discerning cook should be without, Simon Hopkinson's "Week In, Week Out." His Simple Cream of Vegetable Soup is on the menu of my last meal. When fully cooked and puréed its colour falls between harvest gold and avocado green, the quintessential 70s palette. Two bunches of fresh watercress bleed their spring brilliance after an hour of cooking. Hopkinson claims to have learned how to prepare this soup, "as a keen young apprentice at The Normandie, the renowned French restaurant near Bury, Lancashire when I toiled there during a couple of school holidays in the 1970s." [2] It tastes sweet and earthy from the leeks, carrots, mushrooms and watercress, and the slushy texture owes everything to the food mill, not the blender. Given its Normandy roots, the lavish whip cream finish is no surprise. It harkens to another time—of wonderful dinners in French bistros and chefs who cling with fierce pride to the dishes of their youth. The final vegetable soup comes from "The Roux Brothers French Country Cooking." They were a seminal influence during my apprenticeship. I met Michel Roux once, and when I asked him to sign this book (now sadly out of print), he beamed and told me it was his favourite because most of the recipes were his mother's. His eyes were sparkling. Their recipe for Soupe au Pistou has the same Gallic charm. It stands head and shoulders above all other versions. Over time, I have made a few small revisions—I use homemade chicken stock instead of water and cook the pasta separately. The cooking time here is the shortest of the three vegetable soups, so the broth remains crystalline. A final flourish of thick pesto stirred in just before leaving the kitchen is a triumph. It arrives at the table along in an ethereal herbaceous cloud that envelops the eater. I put it on the lunch menu at The Old Prune in Stratford, Ont., and customers waxed poetic about it (and about the goat cheese soufflé from chef Sally Clarke). If there were little in my culinary repertoire besides these three vegetable soups, I'd still be considered a damn fine cook. They're old fashioned, elegant and accomplished and need little else—a good loaf of bread, some fine butter, a piece of ripe cheese, and seasonal fruit to finish. Much is made of modern chefs planting gardens and turning to vegetables as a primary source of inspiration. They all want to be seen with their Blundstones sinking into the dark, loamy earth—a revolution, a modern innovation, like nothing we've seen before. In its subtleties, it could well be. But when I look into a bowl of one of these soups, I see the roots. Where vegetables are concerned, everything old is new again. [1] Hazan, Marcella. The Classic Italian Cookbook. (New York: Ballantine Books, 1973), p. 63 [2] Hopkinson, Simon. Week In. Week Out. (London: Quadrille Publishing, 2007), p. 229 |

Archives

May 2021

© Deborah Reid, 2012 - 2024. All Rights Reserved. Categories

All

|