|

Very soon, food lovers across Canada will seek release from the long winter. Sunshine-filled, warm spring days will tempt them to throw open their doors and take to the woods searching for ramps. In short order, hip restaurants across this beautiful country will be stuffing their menus with this wild green, and ramp chatter will clog social media feeds. You'd think we still lived in a time when salt pork, navy beans, and turnips were all that filled our winter larders.

Ramps, also known as wild leeks, are a perennial wild green that looks like a small green onion but with a broad shiny dark green leaf. I don't like them much (or fiddleheads). I find the flavour too pungent. But I love them in the wild. There's nothing better than going for spring's first mucky walk in the woods, clothed against the damp and chill in a warm and wholly unstylish mix of long johns, worn jeans, layers of lumpy wool sweaters and fleece, and rubber boots—the black kind with the red soles from Canadian Tire. The white light from a clear blue sky, not yet filtered softly through the leafy tree canopy, creates stark contrasts. Mounds of snow turn into grainy crystalline ice piles marking cool, shady places. And, those first licks of green emerge from a dark, loamy soil with a raggedy grey blanket of leaf decay. Walk through them and the air turns sulphuric. Ramps are the first sign of life after the earth's deep, cold sleep. Writing that description is the closest I come to foraging. I learned from having spent my formative years working and living in some of Canada's most beautiful, wild places that we go to the woods to receive, not to take. That doesn't mean that I don't believe in foraging or marking the arrival of a new season with a feast. I love chef Michael Stadtlander's annual Wild Leek Festival. I would happily eat anything (even ramps and fiddleheads) from thoughtful and sensitive forager chefs like Michael Caballo of Toronto's Edulis restaurant, or buy the goods at Jean-Talon market from Nancy Hinton and François Brouillard of Les Jardins Sauvages in Quebec. I trust their connection to the land and know the harvest is mindful. I'm reminded of my first trip to Europe and travelling east by train from Milan to Padova in early spring. Looking out the window at the passing countryside, I'd occasionally catch a glimpse of someone, usually elderly, stooped over in a ditch looking for what I soon learned was Cicoria or young dandelion greens destined for a salad bowl. Later, I enjoyed the mature greens cooked long and slow with lots of garlic at Easter lunch with new friends. It was part of this meal because there were people at the table who knew war and hardship. They knew wild greens made the body robust, kept uncertainty and death at bay. In her essay, Now, Forager, Charlotte Druckman points to the critical role foraging played in the survival of America's Black slaves. She considers the current culinary obsession through this lens and writes, "It's the cavalier misappropriation of foraging as a trend that offends." It's a feeble and desperate connection many modern chefs make to the wild—commercial survival is the driver. How many of them take to the woods with any sense of what is enough or when to stop? The current market appetite can trump the need to leave enough for others or ensure a return next spring. These trend-chasing wannabes are practising what I've come to dub Noma-lite—a shallow rendering of René Redzepi's studied and thoughtful practice. I shudder to think of the abuses heaped on our wild environs in the same way I cringe whenever I see Martha Stewart shilling some craft project that calls for found items from the forest. Amateur enthusiasts often don't know that the wild can be a tender place, lacking a defence against mindless culls. The foragers I know are people who long to be in the wild. That need exceeds anything it will yield. They often prefer the subtle communications of nature to that of humans. They've usually apprenticed to a master, never flaunt their expertise and respect tradition. They know their place and their responsibilities to the cycle of life and death. I'd be happy with less ramp madness this year. I'm encouraging enthusiastic urban dwellers to consume wild goods with a conscience—to eat and enjoy in a manner befitting a finite resource. I encourage everyone, including most chefs, to purchase from speciality purveyors like Forbes Wild Foods in Ontario or leave the preparation of wild ingredients to the few authentic forager chefs. Urban dwellers can take to the woods and virtually trail the masters in the beautiful video series, In The Weeds. When I see bags of ramps sold in posh markets or spot a sauté on every corner bistro menu, I don't want to wonder if those green leaves have been stripped entirely from my first spring walk in the woods. In my second year at the Stratford Chef School, I was assigned as student executive chef for a dinner honouring the great French chef Fernand Point. The dinner was on the last night of classes before the Christmas holiday. On the surface, the menu appeared simple, but its execution required skill and subtlety. I was a perfectionist and hell-bent on achieving Michelin three-star results in a teaching kitchen in rural southwestern Ontario, no matter the strain. I’d fallen hard for Point while doing my research and, crazy as it seems, of all the people I needed to please on that night, I most wanted to get it right for him.

Point steered the course of French cuisine toward the future at his restaurant, La Pyramide, in Vienne, France, moving it away from its often overwrought classical past and toward a sophisticated, lighter approach still recognizable today. He worshipped ingredients and thought they should shine. Flavourful reductions began to simmer alongside the flour-thickened sauces of the past. Elaborate menus were scaled back. Most of the three-star chefs who would later create Nouvelle Cuisine were apprentices in his kitchen—Bocuse, Chapel, and the Troisgros brothers. They were carriers of his lessons and loved him, as did his peers. I’d been in the kitchen until late the night before the dinner, working with the student assigned to pastry. The dessert for the evening was Gâteau Succès. We were busy piping rounds of almond meringue and slow baking them to a crisp finish, whipping buttercream to a light fluff the colour of fatty cream and flavouring it with crushed praline. The success of our pastry prep left me feeling in control and entertaining gilded dreams of the dinner. A bliss that would be short-lived as, the next day, one small detail went astray. The evening’s main course was one of Points most famous creations, Poularde en Vessie, chicken cooked with aromatics in a pig’s bladder. The bladders were the final item to be struck off my prep list and were essential to reproducing the dish with accuracy. I’d written into the evening’s script a grand parade through the dining room of a just-cooked and fully inflated bladder set on a silver tray, just like the pictures I’d seen in historical cookbooks. I’d ordered the bladders from the local European butcher well in advance, and they seemed pleased to fill my unusual request. Before heading to the restaurant in the early afternoon of the dinner, my last stop was to collect them. Mr Weideman and his son Daniel presented me with a long strand of bladders, blown up like balloons, and strung together like something out of a Hieronymus Bosch painting. The holiday riot of their delicatessen lost its coloured-foil lustre as I instantly realized they were too small. I’d had to paste a smile on my face big enough to conceal my disappointment. With bulging shopping bags in each hand, I headed out into wet, heavy snow that clung to my boots with the weight of the failure stuck in my head. The stainless steel sky tinged the town the colour of my despair. My mind was racing to find a solution to a problem that had come on like the flu. The kitchen was empty when I arrived at the restaurant. I’d planned time to review my orders before the day’s activity began. By nature, I am tightly wound, but my nerves clanged like sauté pans heaved into the dish pit during service on that afternoon. I took pride in being fastidious and yet one of the details I’d attended to with such care had gotten away. I couldn’t think what to do about the bladders and settled on hand-wringing. When the teaching chef arrived, he could read the distress on my face. We set the crew to work, and the chopping and hustle calmed me. The chicken would be cooked for dinner service, so we had the luxury of a few free hours. Out of the blue, the chef wondered aloud if Ziploc bags could substitute for the bladders. We had enough time and ingredients for a trial run. I put a large stockpot of water on to boil while someone ran off to the store to buy the bags. We needed this solution because we didn’t know that pig’s bladders vary in size and shape. The bladders I received could accommodate a small bird like squab or pheasant but certainly not a chicken. The bag containing the chicken, liquor, and aromatics stayed suspended in the barely simmering water bath. The ethereal scent of the bird when it emerged from the bag shattered my worry—it was succulent with the flavours of cognac, Madeira, and black truffle. In late December of 1991, long before the advent of modernist cuisine, we had invented a primitive form of sous-vide cooking. The Ziploc intervention worked a charm. We all exhaled, and the rest of the night’s prep was done with ease. The first course, gratin de queues d’écrevisses, was a luxurious dish of langoustines in a shellfish reduction, rich with cream. It took Point seven years to perfect this dish. The chicken was garnished with glazed baby root vegetables from a local farmer. Saint Marcellin cheese followed, wrapped like a gift from nature in chestnut leaves, perfectly ripe and earthy. With cheeks flushed from the heat of the kitchen, I was giddy with the success of the evening as the last dessert left the kitchen. Something important had happened to me. On that winter night, in the tender, early days of my development, I had fallen truly and deeply in love with French cooking. I spent the next decade pursuing its masters. As I passed through the dining room greeting the guests, several told me that Fernand Point was smiling down on me. I recognized the compliment as a generous offering to a young cook, but I also knew in my heart, having passed the test of recreating the work of a great master, it was true. I'm up today at 6 a.m., and early rising is not me. I love the night and fit easily into the rhythms of the restaurant business. Working until midnight, falling into bed at two or three in the morning and sleeping until after eleven is heaven.

I recall a time not so long ago when I slept like a babe in arms. Sleep's a new frontier for this woman at mid-life. I've decided it's futile to rail against this current state and try to accept it. So I'm up and writing at daybreak, an hour some writers proclaim the most creative. Do my nocturnal leanings disqualify me from this profession? There's a magnet on my fridge that reads: "Only dull people are brilliant at breakfast." God bless Oscar Wilde. The restlessness I'm feeling is more pervasive than just this one night. It's an energy shot through late winter when all northern dwellers grow weary of the snow and cold. My landlord switched from salt to sand for roughing the surface of the slick ice outside my door. The grey-brown on my walkway seems to sum it all up. Dirty pools of sand and snow melt to a muddy slurry on the white tiles in my foyer—how I long to wash it all away. I rushed outside into brilliant sunshine two days ago, walking directly into its warming rays. The light buoyed my flagging spirit and, for a moment, made an early end to this season seem within reach. The temperature rise softened the snow and ice underfoot making it crumble like shortbread as I walked. Out on the street in Bloor West Village, people unzipped their jackets and were soon carrying woollen hats and gloves in hand. I've been thinking about my bike and warm night rides in the streets between my house and the Humber River. I've put my name on a waiting list for a garden allotment in High Park but won't know until April if I'll plunge my hands into the earth. I push down the desire to purchase dahlia tubers with wild abandon, imagining myself sitting in the shadow of their tall, stocky, multi-coloured flower heads in late summer. I'm stuck between the oppression of this endless winter and the too-far-off promise of spring. This cold season can't pass quickly enough for me. March surely must bring relief. The sun will hang high in the sky long enough to trigger epic melts. Snowbanks will begin to recede, exposing a dirty and dormant terrain. My restlessness finds temporary relief in marmalade making. I've pulled from my shelf a book whose title, Saving the Season, makes me chuckle. I like marmalade, and it was the appearance in my local store of Seville oranges—with their distinct skin like cellulite on ageing dames—that reminded me of this kitchen pleasure. I have a great recipe from Sally Clarke, one of Britain's best cooks, using this prized citrus fruit from Spain. But the truth is, orange marmalade is not my favourite. I prefer lemon and, when marmalade of my own making is in short supply, I buy Robertson's Silver Shred. There's something less bitter, more acidic and fresh in preserves made with lemon. I have a recipe for a quick marmalade using Meyer lemons. I love their sweet-tart flavour and their skin is thin and tender and suited to a quick-cooking preserve. I can imagine the marmalade's orange translucence with bits of soft, saturated citrus fruit suspended in it. I've also settled on making something new: Fine-Shred Lime and Ginger Marmalade from Kevin West's extraordinary book.[1] It's a three-day process, just the kind of project that will chip a few more grey flannel days off the season. I learn from West the spongy white pectin-rich pith that cushions the delicate inner fruit is called the albedo.[2] There's something in the tumble of language he uses to describe the results that rally my enthusiasm, making my mouth water in anticipation. This marmalade, he writes, is "a translucent mass suspending a tumult of finely shredded green peels—and the powerful flavours of raw lime and ginger become elegant through dilution."[3] It's a preserve tinged the delicate green of spring hope. There's a Marmalade Cake I want to try, imagining spectacular results using lime preserves instead of orange. I know marmalade making is the right task for today. It will ease my weariness and leave me with the impression of productivity. I'm going to set out in search of the ingredients after another cup of coffee. The city has issued an extreme cold weather alert (too many of those this year to track). There's a storm bearing down on Toronto that's promising to wreak havoc on our already frazzled systems. Today I'll gather fruit from far-off sunny places and shake my wooden spoon at this fierce season. Winter be damned! On the horizon, there's the promise of sweeter, brighter, fresher things in my kitchen. [1] Kevin West, Saving the Season (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2013) 477. [2] Ibid. 477 [3] Ibid. 477 I began my cooking career in fine French restaurants in the mid-80s when the revolutionary ideas and techniques of France's Nouvelle Cuisine were trickling down into Canadian kitchens. One of the most significant changes involved cooking vegetables—green ones in particular—for less time to retain their vibrant colour and pleasing texture. Anyone overcooking vegetables, so all their natural appeal was discarded with the cooking water, was thought déclassé. (Exemptions were made for grandmothers. Who dared to tell them times had changed?)

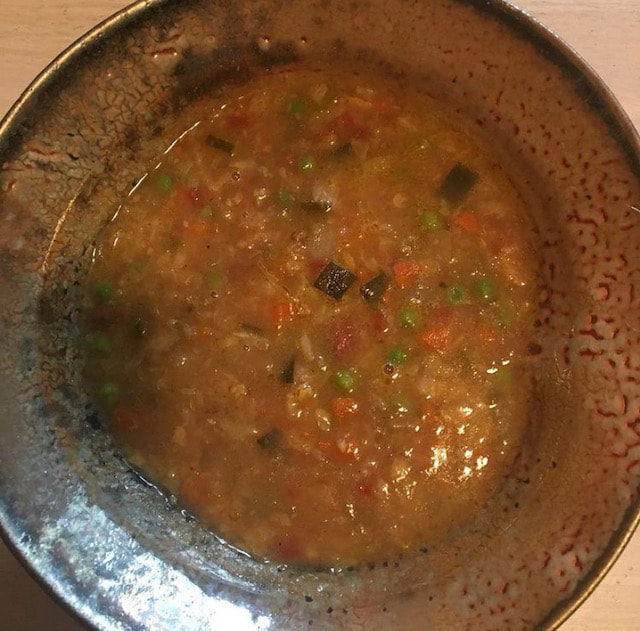

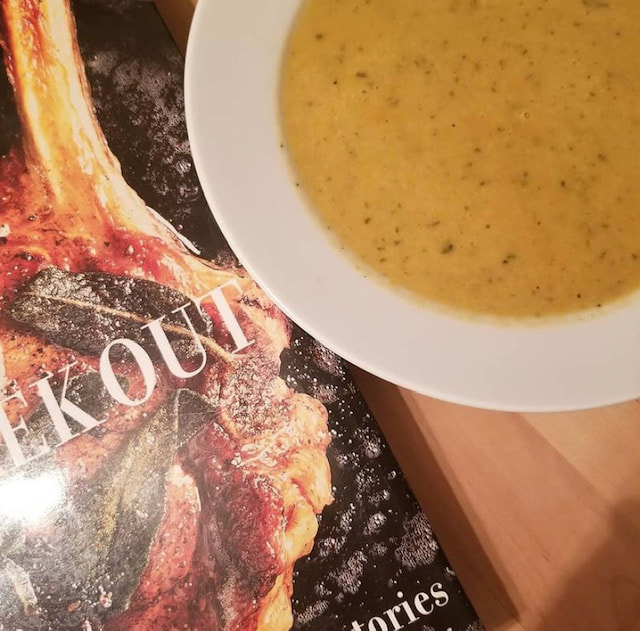

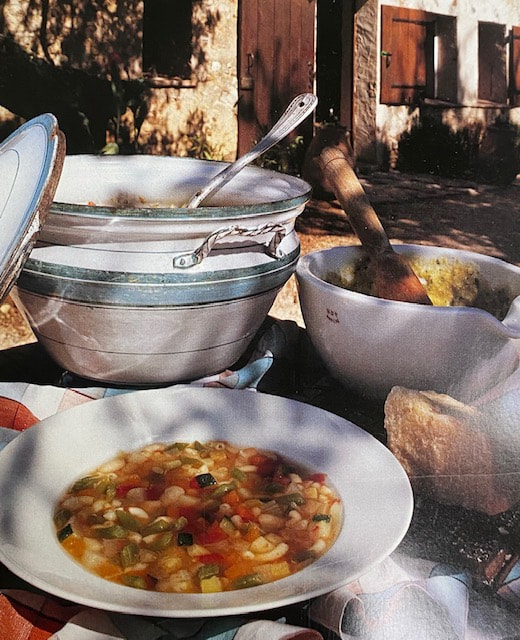

Cooking vegetables perfectly requires skill. It's as disconcerting to crunch into a vegetable more raw than cooked as it is to eat those killed through overexposure to heat. When a fork or knife can't penetrate, things get messy and carrots or broccoli shoot like missiles across the table. But there are times when vegetables are best cooked to completely tender. There's an essential pleasure in simmering or stewing them well beyond reason to a rich vegetal concentrate. Often the French call these dishes paysanne to signal their deep agrarian roots. Three vegetable soups deliver this kind of simple enjoyment to me. They're not the vibrant green or exotically spiced purées of celebrity chefs. They're made with little more than fresh vegetables, good stock, salt, and pepper to season. The first is Marcella Hazan's Minestrone di Romagna. I cooked it the day she passed, as a tribute. A mixture of hardy roots and tender green vegetables are simmered over low heat for three hours. Miraculously most of them retain their shape while hovering perilously close to the edge of deterioration—at the end of cooking discernible cubes of potato and zucchini, remain along with the green beans. The vegetables that meld into the soup are the sliced caramelized onions, the first in the pot, and the shredded Savoy cabbage, the final addition. They add sweetness and form a tender, soft mush, the soup's underbelly. It's the kind of humble, nourishing meal found in the farmer's bowl in the painting, Il Mangiafagioli (The Bean Eater) by Annibale Carracci. Marcella writes the soup, "has a mellow dense flavour that recalls no vegetable in particular but all of them at once."[1] Her descriptor perfectly suits another soup I adore from a book no discerning cook should be without, Simon Hopkinson's "Week In, Week Out." His Simple Cream of Vegetable Soup is on the menu of my last meal. When fully cooked and puréed its colour falls between harvest gold and avocado green, the quintessential 70s palette. Two bunches of fresh watercress bleed their spring brilliance after an hour of cooking. Hopkinson claims to have learned how to prepare this soup, "as a keen young apprentice at The Normandie, the renowned French restaurant near Bury, Lancashire when I toiled there during a couple of school holidays in the 1970s." [2] It tastes sweet and earthy from the leeks, carrots, mushrooms and watercress, and the slushy texture owes everything to the food mill, not the blender. Given its Normandy roots, the lavish whip cream finish is no surprise. It harkens to another time—of wonderful dinners in French bistros and chefs who cling with fierce pride to the dishes of their youth. The final vegetable soup comes from "The Roux Brothers French Country Cooking." They were a seminal influence during my apprenticeship. I met Michel Roux once, and when I asked him to sign this book (now sadly out of print), he beamed and told me it was his favourite because most of the recipes were his mother's. His eyes were sparkling. Their recipe for Soupe au Pistou has the same Gallic charm. It stands head and shoulders above all other versions. Over time, I have made a few small revisions—I use homemade chicken stock instead of water and cook the pasta separately. The cooking time here is the shortest of the three vegetable soups, so the broth remains crystalline. A final flourish of thick pesto stirred in just before leaving the kitchen is a triumph. It arrives at the table along in an ethereal herbaceous cloud that envelops the eater. I put it on the lunch menu at The Old Prune in Stratford, Ont., and customers waxed poetic about it (and about the goat cheese soufflé from chef Sally Clarke). If there were little in my culinary repertoire besides these three vegetable soups, I'd still be considered a damn fine cook. They're old fashioned, elegant and accomplished and need little else—a good loaf of bread, some fine butter, a piece of ripe cheese, and seasonal fruit to finish. Much is made of modern chefs planting gardens and turning to vegetables as a primary source of inspiration. They all want to be seen with their Blundstones sinking into the dark, loamy earth—a revolution, a modern innovation, like nothing we've seen before. In its subtleties, it could well be. But when I look into a bowl of one of these soups, I see the roots. Where vegetables are concerned, everything old is new again. [1] Hazan, Marcella. The Classic Italian Cookbook. (New York: Ballantine Books, 1973), p. 63 [2] Hopkinson, Simon. Week In. Week Out. (London: Quadrille Publishing, 2007), p. 229 (I was talking to a colleague and friend recently and she told me about receiving terrible treatment from the same Toronto recruiter I mention at the top of this note. He consistently fails to put women into positions in line with their talent. I can only hope his paycheque is as small as his imagination. The original note was written in late 2018.)

A young woman I mentor is actively searching for an executive chef position (I'll refer to her as A). She spent ten years working in great restaurant kitchens in Ontario and Montreal, has European training, was executive chef at an island retreat for global political and corporate leaders and led a unique food project in South America. What she hasn't done—what so many women haven't done—is follow the path of the traditional brigade system. And that stumps a lot of men who are hiring. We met recently, and she told me a couple of her job search stories. I'm sharing what I said to her below. Looking squarely at the ways we keep women out of the top spot in the kitchen is one step toward change. When I hear a chef bemoan the shortage of talent in our industry, A's story is one of many that jump to my mind. Dear A: When a man in a position to hire tells you he is struggling to see how you fit in the business, at a time when you're ready for an executive chef position, look on him as a dangerous gatekeeper. He's delivering a message that's been spinning for female cooks for ages. What he’s saying is you don't belong. It's not entirely true he couldn't see a place for you either. He sent you line-cook job postings in mediocre corporate roadhouses. When a juicy position that was a perfect fit came up, he told you it was a long shot. Look on this as a measure of his lack of talent, not yours. And when an executive chef leading multiple restaurants tries to convince you to become an executive sous chef (as if the job title isn't warning enough), remember a lot of men like women in that position. It works for them because it follows the traditional order of men on top. They parade women sous chefs around at events as evidence of their wokeness. But sous chef today is a position reminiscent of pastry and garde manger when I was an apprentice. It’s a place where a lot of female talent gets parked indefinitely. He also thinks so little of your decade of stellar experience he wants you to come in and do a stage to decide if you're a good fit. Stop and ask yourself if he's getting men with similar experience to jump through that hoop? They'd tell him where to get off and so should you. Sadly, there's no shortage of men continuing to participate in toxic masculinity—recruiters and executive chefs who came up through the brigade system and slavishly still cling to it. Instead of getting rid of a broken military model, they make a problem of anyone who doesn't fit it. Few are the men who possess the courage to change, and many are the men who pay lip service to it. But don't think we can't see the ways they plod along serving their brothers and the status quo. When you hear the message, you don't belong, in all of its gross and sly manifestations, RUN. THE. FUCK. AWAY. Do not internalise it. Take too much of it in and pretty soon you're talking yourself out of your greatness. Just know the barriers thrown up against women moving into a position of authority are still formidable. Let us take pleasure in dining out on these stories. We must warn our female colleagues about these men. Hold out for the people who recognise and want your kind of special. Sadly, along the way, you'll have to show your back to plenty of unworthy gatekeepers. It's not your job to teach some men how to be decent humans and leaders, but don't pass on the opportunity to point directly to the problems with their offers. Please, put me on speed dial for those rare occasion when your confidence falters. |

Archives

May 2021

© Deborah Reid, 2012 - 2024. All Rights Reserved. Categories

All

|