|

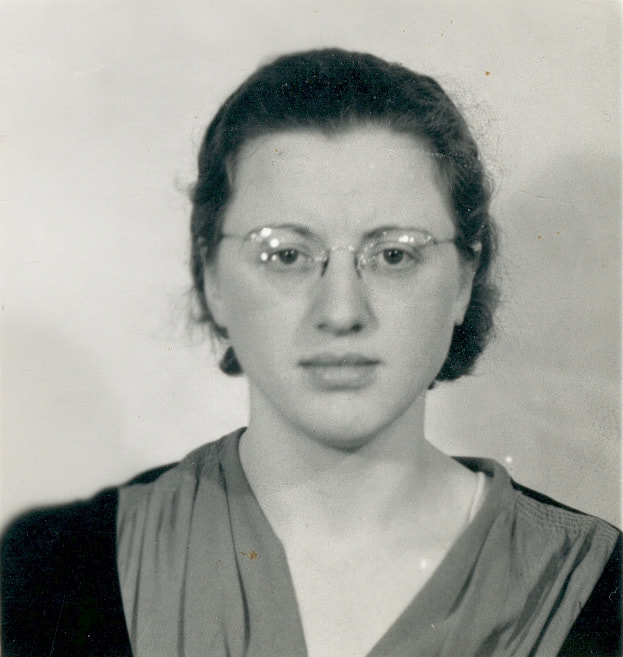

That's my grandmother, Theo Mercier, caught as the shutter closes—leaning forward, squinting at the camera, supporting her weight on the back of a deck chair, a cigarette between the fingers of her right hand. Her uniform crisp with starch and smooth from a hot iron—bright white against the lumber piled around her. The wind off the water lifts her apron and ruffles the hem of her dress. Behind her, two young men raise a rondeau cooking pot, framing her head with an aluminium halo. The photo was taken between 1934 and 1939 on the S.S. Easton, a coal-fired bulk freighter. It carried pulpwood, grain, and coal along the St. Lawrence upstream into the Great Lakes and back out to ocean-going vessels in the Gulf. In her early 20s, she was the cook. In the crowded galley, she would have been a commanding figure at five foot eleven. The men in the photo were her crew. Some, maybe all, would have been transient, earning their keep on the way to lumber camps and pulp mills or leaving rural villages for the promise of work in cities like Montreal or Toronto. Theo would have hustled them along as they cut beef chuck for stew, peeled potatoes, washed dishes, or whisked Bird's custard powder into boiling water and layered it with canned fruit into parfait glasses. I imagine them hauling fresh supplies bought at the newly opened Atwater market in Montreal, back to the boat along the Lachine Canal. Following in her wake up the stairs for pork, poultry, and boudin noir and then downstairs for vegetables—new potatoes, fat leeks, big heads of cauliflower and broccoli, squash, and apples for fritters and crisps. When I first saw this image about a decade ago, I was touched by what we had in common. Until that point, I did not know about her early life. Theo was a cook, like me. Her skill at the stove was a talent of value on boats. There are recipes from that period in the two handmade cookbooks I have of hers in my kitchen. The crew on the Easton might have enjoyed fricassee of veal, chicken pot pies, golden breaded pork cutlets with applesauce, omelettes for breakfast, or ripe, cold tomatoes stuffed with liver pate. In one of the cookbooks is a pamphlet from 1930, The Magic Cook Book. She circled a recipe for Sour Milk Biscuits made tender with butter and lard and baked quickly in fierce heat to an airy lightness. They cost pennies to make and would have been filling with a bowl of her soup—made from scraps and leftovers and tasting like riches. The American writer and naturalist Henry Beston wrote about life along the river in his book, The St. Lawrence. About the local cooking, he writes, "There is no more excellent cooking of its kind than countryside French-Canadian. French provincial in its tradition, simple and good in its recipes and wisely skilled in its simplicity, it lives wholesomely and well from its resources of farm and field…A particular touch of Old France is the excellence of the omelets; you can get a good omelet anywhere, not the whipped-up egg-foam monstrosity, but the true French thing, the small omelet of tradition beaten with a fork and fried in country butter. Serve this with a wedge of honest, home-baked bread, a pat of butter to one side, and a bittock of homemade wild strawberry jam, and one's hunger and weariness make their own grateful prayer." *** The cargo on deck of the S.S. Easton might be a clue as to the boat's location (coal coming from England might have been in the holds below). Canallers with French Canadian crews carried pulpwood from lumber camps along the shores of the Lower St. Lawrence to mills like Consolidated Paper Corp. at Trois-Rivières or further west to Montreal. During that period, boats with similar cargo can be seen in the Lachine Canal. The Easton worked the same stretch in the 1950s, carrying supplies to build the Quebec North Shore and Labrador Railway. Maybe it was in the Upper St. Lawrence between Kingston and Montreal. Historic film footage from the 1930s shows a coal-fired caneller on the river near Prescott, Ontario, and another waiting to go through a lock. Or it could have been on a Great Lake like Michigan, near the shoreline seen in the distance. There's a record of the Easton arriving from Montreal at Manitowoc, Wisconsin, on Friday, October 25, 1935. My grandmother was not the only woman cooking on canellers during the depression. I like to imagine her crossing paths with other women in ports. Maybe on that Friday in Manitowoc, Theo and another cook smoked cigarettes and swapped stories and recipes over a burger at The Beacon Lunch. *** Theo needed to earn a living. She had a baby back home, being raised by her parents as their own. Later there would be bills for boarding school. At the time, French-Canadian Catholic families with daughters who were young unwed mothers were expected to step in. Adoption would not be a real option for another twenty years or more. Unwanted children went to orphanages. The circumstances were terrible, and good choices were in short supply. There must have been an understanding between all of them that the odds of finding a man and securing a future were higher if she were away, without a child. At home, her story would have been shared in whispers. If it was a strategy, it worked. The young woman squinting at the camera met Harry Reid, an apprentice in the engine room. He was a gem of a man. I can't imagine what the conversation about the truth was like between them. He saw things in her he liked. My grandmother spent a good part of her 20s working on boats on the St. Lawrence River and Great Lakes. Those early days of autonomy, adventure, and new love helped reshape her wounded spirit. In the galley of a caneller, Theo got to experience life as a young free woman. There's something sad in her eyes. Or maybe it's what I want to see. Look at her full lips—a high-spirited young woman, felled at the knees. I want to wrap my arms around her. Tell her everything is going to be okay. *** Theo was a young woman with a sexual appetite. Nineteen years of age. Full of desire. Sometime in late October or early November 1932, she had sex. I hope there was pleasure that it didn't all come down to pressure. Or thirst for a virgin. Please let it have been more than once. *** "Illegitimate pregnancy may be a sign of inability to meet satisfactorily the pressures and responsibilities of adulthood. Like stealing, setting fires, and difficult behaviour in school, it may be a symptom of a fundamental problem." *** The catholic church in the 1930s—averting their eyes to acts of infanticide performed by their congregants and faithful servants.* I shake my head at Theo's loyalty to that institution. All her life, she sat six-rows from the front at St. Kevin's in Welland—belting out the hymns in alto. Maybe it was her vengeance. There she was reminding them every Sunday she'd done pretty well for herself. *** Théophilta means friend of God in Greek. She was a fille-mère. A sinner. Not sinned against. *** When I began to search, I lived a two-block walk from the hospital where her son was born. July 11, 1933. Eighty-eight years ago, today. The proximity shook me. It felt like she was speaking things she couldn't in life. Was she with les soeurs de miséricorde on Jarvis, or did she escape their vicious grip? A block up the street was Toronto's Hospital for Unwed Mothers—Grace Hospital today. At the time, there was a residence for young women attached. I phoned the Salvation Army looking for information, hoping to find evidence. But the records were lost in a fire in the 40s. About all else, they were vague. At every step of the way, shame and silence. *** "A young girl's sexual development was supposed to lead only to the altar; abstinence was not presented as a choice but an obligation. It's hard to imagine most girls who were hidden away in homes coming out without a distorted view of sexuality." *** The man was a daredevil. Went over Niagara Falls in a rubber ball. Hawked pieces of it to earn his keep—a bonafide local celebrity. I phoned the head office of Ripley's Museum in Florida. They sent me photos. The moment I saw him, I knew. I was looking at my uncle. More than two decades her senior. His wife and family in Philadelphia. No barriers to pursuit. *** "Then, as now, help for unwed mothers was not a popular tax expenditure. For the small subsidies governments gave to the homes, every province required the father to be named, so he could be tracked down and made to pay." *** I wonder how much rubber that took. Or if he even bothered. Father isn't the correct term for an absent man. *** "I had to give up my last name for the rest of my stay…the only other identifying feature was my due date." *** Anonymity is a detail that breaks my heart. To protect the family name. So there's nothing permanent. And to speed the forgetting. *** "The babies left behind had few takers in the Depression and war years, and they ended up in huge orphanages run by a religious order." *** Theo's family stepped in. Her baby boy stayed within reach. His early history was fiction. To save face. And to give Theo some freedom. *** I inherited a tea set from her—Royal Crown Derby Blue Mikado. It came in a cardboard box wrapped in pale yellow tissue paper velvety soft from time and wear. Likely ordered from the Eaton's catalogue. A gift from the daredevil. *** Did she imagine a union where she could host afternoon tea? Poundcake crumbs on a plate painted with the scene, 'sad-eyed wandering lover.' The dishes were always in plain sight in a cabinet in her dining room. There was something she wanted to remember. *** The photo below is from 1935—two years after his birth. That smile. I feel relief. She made it. Working on the St. Lawrence River. That's where she met Harry. A gem of a man—soft and kind-hearted. Just what she needed. They made a good life. *** "Some of my ambition came from the determination to put it all behind me. But despite any success I had, I was always fearful and nervous. I often had what I called "emotional problems"—panic attacks and long bouts of anxiety." *** We never talked about it. There were grown-up whispers. But no details. I asked a family member if distant relatives who were still alive would talk to me. No, they were good French Canadian catholics. She never talked to the people who loved her the most. Went to her grave with it. Left behind an unspoken inheritance. Early in my cooking career, I spent six weeks studying in Boston. About a month into my stay, I went to see “Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould.” I remember sitting in a dark theatre mid-afternoon on a weekday (I still do that), watching scenes filmed in Northern Ontario and experiencing the heartache of homesickness. It caught me entirely off guard. I’d never felt such a yearning for Canada (and I’d been on longer journeys). My time in Boston was enjoyable, and there was no catalyst for it, but I longed for the place I was from. The next day I told a pastry chef friend—a Bostonian—who told me she’d heard other Canadians express similar sentiments. She went on to say that Americans had mastered the big patriotic talk, but Canadians knew the walk. I can’t speak to the integrity of her opinion. To say I love Canada sounds thin and brash. Love of a place isn’t that simple. It’s hard to explain the deep feelings that run through me, as mysterious and vital as the need to breathe. It’s an emotion that bubbles up unexpectedly and is difficult to conjure at will (like real gratitude). I’m 12th-generation Canadian. My great grandfather’s family arrived in Quebec in 1647 having journeyed by sea from their home in Tourouvre, Normandy. They were among the second big wave out of France and established themselves near Quebec City at Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré. The foundations of Julien and Marie Mercier’s home are still there. I’ve yet to attend the annual reunion, but family members who have gone are overwhelmed by the gathering size. Good Catholics, the Mercier’s were prolific. I doubt any of that accounts for my national attachment, but there are other indications my passions are an honest inheritance. When I was a small girl, dinners with extended family happened regularly, and seriously animated conversations took place under the influence of 70s-style drinking. Raucous arguments concerning Canada’s governance ranged despite the fact most at the table shared liberal leanings. Often these were conducted in a tangle of French and English, enhancing the rowdiness. The generation who spoke French at the table never insisted their children adopt it. When my family wasn’t erupting over current affairs, they wrestled with the other topic that bound us all together, food, and those conversations were no less lively. My friends who found themselves at our table were astonished. I recall a university roommate who told me she’d never heard so much food talk while people were eating. She said it as if it was a failing like we practised a rare and perverse branch of gluttony. My grandmother, the family matriarch, was smart, well-read, adventurous, emotionally detached, and lacking in tender, maternal leanings. Theo (short for Adeline-Rose-Theophilta) found disinterest in, or indifference to, food and country intolerable. Being hungry and staying abreast of current affairs were less painful than suffering her disapproval. To be among them and be loved, I had to acquire the same skills—I had to eat and be interesting. My grandmother had tremendous skill in the kitchen—a hard-won talent given her mother was a terrible cook. Theo had no childhood memories of the luscious sweet amber liquid from baked beans bubbling over from a cast-iron camp oven on a wood stove. No pork roasts basted to crisp golden perfection, or sugar pies with lard crusts that flaked when the fork hovered over it. Those visions of the Québécois culinary past are largely force-fed. It certainly wasn’t the experience of a young girl living on a rural homestead in St-Augustin-de-Woburn in the early 1900s. I think my grandmother developed her culinary muscle as a way to distance herself from the harshness of her childhood. It was one of the ways she could assert her independence. How she came by those skills is still largely a mystery. Toward the end of her very long life—she died in 2004 aged 91—she was desperate to tell her story, never more than when under the influence of her third bourbon Manhattan. I couldn’t listen under those conditions because I had a sense it was too important. Also, I was returning a serving of the indifference she’d shown me over the years. I was mostly blind to the force animating her small kitchen—cooking was a stand-in for hugs and kisses. It worked. I often dragged my feet on the journey to her table, but once my knees were under it, I wholly embraced my delicious fate. Maybe she began to take an interest in food as a young girl at the tables of better-fed friends, a reminder of the sorry state of her family meals. It’s more likely during a difficult period in her early adult life when she found herself employed as a chambermaid by a wealthy family in Toronto—a suitable distance from her chaste Catholic home—she began to learn from the cook in residence. For a time, she cooked on ships on the St. Lawrence and the Great Lakes where she met my grandfather, an apprentice in the engine room. They married and moved into a small French neighbourhood in Welland, Ontario. This densely populated area housed international labourers who worked in the shipyards in Port Colbourne and the local steel and cotton mills. My father and his siblings remember the character of Asher Street as like a little United Nations. It was not beyond Theo to knock on the door of a house emitting a particularly delicious aroma and inquire after its origins. Many times I’ve found myself in that same situation, but lacking her chutzpah. What better way for women of diverse cultures to forge a bond? My grandmother had an abundance of curiosity, and it was that, not books, which built her skill. I know having inherited the two small cookbooks, one of her own making, that were her only companions in the kitchen. From Theo, I inherited a love of boudin noir long before I knew what it was. Nothing made breakfast better than its soft dark richness nudged up against sunny side up eggs. No-one in my family can imagine Christmas Eve without tourtière, and we all agree on the perfection of her soups. I don’t want her back, but I love her enough to want to stick to the truth, including the messy stuff. Love between people is as complex as love of place. My most tangible inheritance from Theo has been the web of deep feelings for country and food. And just like my experience in that Boston movie theatre, separation lets me hear my heart’s longings loud and clear. |

Archives© Deborah Reid, 2012 - 2024. All Rights Reserved. Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed